Thought For The Day

Thought For The Day

FoBo

Peter Jakobson Junior of Jakobson Realtors is looking very carefully through my royalty statements. 'The Loneliness Of Lift Music,' he muses, 'that's an interesting title. The reason I'm looking at all this so carefully, Nicholas, is that here in New York we have a lot of people who would like to be musicians, or writers, or whatever, but who aren't making a living at it. So I just need to see that you're the real thing.'

I laugh conspiratorially. I want this guy to rent me an apartment in an area which was once funky but is now just expensive, which was once creative but is now plastic, which was once a place of production (studios) but is now a place of consumption (boutiques). 'Ah yes, all those waiters who are really actors,' I say, mustering just enough pity and scorn to indicate that such suffering and poverty, such down and dirty bohemia, is far behind me now. Which it is. But maybe it's in front of me too.

Folk Art Is Open Source

'If a thing's worth doing, it's worth doing badly (baby)' sang Green of Scritti Politti. You could add that if a thing's worth doing, it's worth doing for no money. A phrase that seemed to keep coming up at the New York Expo music and technology conference earlier this month was 'ancillary revenue streams'. As in Q: How can artists survive in a post-copyright age, where their music may well be given away online for nothing? A: Ancillary revenue streams. Which means that even if the music's free, you can still sell people T shirts, or put banner ads on your website, or get paid to present the Grammys, based on your status as a cult music maker.

'If a thing's worth doing, it's worth doing badly (baby)' sang Green of Scritti Politti. You could add that if a thing's worth doing, it's worth doing for no money. A phrase that seemed to keep coming up at the New York Expo music and technology conference earlier this month was 'ancillary revenue streams'. As in Q: How can artists survive in a post-copyright age, where their music may well be given away online for nothing? A: Ancillary revenue streams. Which means that even if the music's free, you can still sell people T shirts, or put banner ads on your website, or get paid to present the Grammys, based on your status as a cult music maker.

The breakdown of copyright in the digital age is taking us back to folk art and the oral tradition. Digital folk art. Open source.

Anon (Trad. Arr.)

In one of my narratives for The Earl Of Amiga Presents Electronics In The 18th Century I talk about Linus Torvalds, the Finnish programmer whose free and 'open source' operating system, Linux, is the world's fastest growing. IBM have just announced that they are to make it their OS of choice, which is more bad news for Microsoft. In my tall tale about Linux, word reaches the 18th Century that Linux is open source, which means that anybody can extend or debug it on condition that they forfeit intellectual property rights for their improvements.

In this way Linux, like the internet and like oral literary traditions, uses the power of 'distributed intelligence': millions of ordinary computers all over the world crunching numbers, each concentrating on a small corner of a problem, can beat one centralised supercomputer (or author). Just like oral poetry or the kind of folk music which gets credited to Anon. (Trad. Arr).

In my sketch Goethe, Dr Johnson and King Ludwig of Bavaria don't quite know what an operating system is, but they have strong convictions about what any new gizmo should contain. Dr Johnson says that grammar and etymology are important, so he contributes a dictionary with grammar and spell checkers. Goethe is obsessed with colour theory, so he insists there should be coloured icons. And Mad King Ludwig is fixated on the idea of matching the splendour of the Palace of Versailles, so he insists on adding hundreds and hundreds of windows. Thanks to these men's rewrites, Linux gets turned into Windows 3.1. Boom boom!

Media Content Creators From Mars

Are we really returning to folk music? Is art going to be communal, copyright unenforceable? Am I one of the last people to make a living from ideas?

Are we really returning to folk music? Is art going to be communal, copyright unenforceable? Am I one of the last people to make a living from ideas?

Mostly what I do when I'm not performing as the Earl Of Amiga is apartment hunt. I go to New York neighbourhoods with an arty ambience and I look for To Rent signs. New York has many arty neighbourhoods. My first choice was the Lower East Side, where tenements originally full of Jewish immigrants from Europe have been occupied by hispanics. More recently this area, called East Of Essex or LoHo, has been infiltrated by arty hipsters. Or, as an article in this week's Village Voice calls them, media content creators.

This rather bitter article talked about the 'boutiquification' of the area, and pointed out that real estate agents often have framed pictures of the colourful Spanish-speaking poor or green-haired subcultural types in their lobbies to advertise to affluent media professionals just how funky and edgy it is. But, just as in tourism, these thrill-seeking insurgents will eventually push rents too high for poor families or pioneering bohos to afford, and colourful places like the Essex Street Market will be filled with vendors of odd hats, designer lamps and ironic inflatable furniture.

It's the invasion of the media content creators from Mars. Luckily, everybody in the US is from Mars (or somewhere foreign) anyway, and everybody who arrives here gets richer than they were back there, so invasion and yuppification are not things anyone wastes a lot of time complaining about. (Except the odd snobby boho in the Village Voice.)

What Is Fobo?

FoBo is Faux Bohemia. It's rich people deciding to slum it and live amongst the poor, only to force the poor out of the area. It's rents skyrocketing because an area is being occupied by artists (who only, poor dears, went there in the first place because it was such a godforsaken wilderness where even people who made virtually no money could pay the rent). FoBo is those same areas a few years after their embourgeoisement, sporting an increasingly tame and plastic air of radical bohemia. It's a fading memory of cutting-edge relevance. It's a Greenwich Village coffee house, it's a SoHo loft.

FoBo is Faux Bohemia. It's rich people deciding to slum it and live amongst the poor, only to force the poor out of the area. It's rents skyrocketing because an area is being occupied by artists (who only, poor dears, went there in the first place because it was such a godforsaken wilderness where even people who made virtually no money could pay the rent). FoBo is those same areas a few years after their embourgeoisement, sporting an increasingly tame and plastic air of radical bohemia. It's a fading memory of cutting-edge relevance. It's a Greenwich Village coffee house, it's a SoHo loft.

I wanted to say in this essay: 'It's easy to scorn FoBo. But FoBo is good! Let's celebrate all that tacky boho kitsch! Let's celebrate precisely that moment at which 'Bo' becomes 'Faux', and what's self-righteously 'real' becomes plastic and fake. That crucial crunch point where production meets consumption, outsiderdom meets insiderdom, and radical chic becomes, simply, chic. That's the new cutting edge!'

FoBo happens because, in a city like New York, this crazy game of Musical Chairs is happening all the time. The muse (or human creativity) has to sit down in a different chair each time the music fades. So different districts get this aura of credibility by association with the muse, or with important artists of a certain decade. It's what Pierre Bourdieu would call 'cultural capital', and Angela McRobbie would call 'subcultural capital' or simply cool.

Areas with cultural capital go up and down on a stock exchange which follows the current market value of the artists they're associated with. And realtors selling or renting properties in these areas are totally aware of these values.

The Village Voice is a fairly FoBo publication itself. Like Greenwich Village, the 60s protest area of folk clubs and coffee houses which gives the paper its name, it is becoming a plastic, tourist- and consumer-friendly version of its formerly radical self. Bleeker and McDougall Streets were once the haunt of young method actors and superstar folkies like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. (Dylan, of course, went FoBo when he went electric. Or was it when he went acoustic again, or country, or Christian?) The chess-playing students are still there, but now the coffee houses are flanked by tacky tourist traps like the ones you find on Carnaby Street. And these days the Voice is free, financed by what seems like hundreds of pages of advertising.

When Exactly Was The Golden Age?

The Voice article about the 'boutiquification' of LoHo assumed the tone of all Golden Ageists and Holier-Than-Thou pioneers. It basically said that the area was once, for hipsters at least, a kind of wild frontier. When Reed and Cale lived on Ludlow Street they had a cold water walk-up. They stole electricity from next door through a secret cable. Now the place is full of 'media content creators' taking refuge from the multimedia companies of the Flatiron District, or Financial people cashing in on the proximity to Wall Street.

The Voice article about the 'boutiquification' of LoHo assumed the tone of all Golden Ageists and Holier-Than-Thou pioneers. It basically said that the area was once, for hipsters at least, a kind of wild frontier. When Reed and Cale lived on Ludlow Street they had a cold water walk-up. They stole electricity from next door through a secret cable. Now the place is full of 'media content creators' taking refuge from the multimedia companies of the Flatiron District, or Financial people cashing in on the proximity to Wall Street.

Of course, as with all such authenticist snobbism, you have to say 'Well, when exactly was the Golden Age, and who exactly are the Salt of the Earth?' Was the area only relevant while it was in the hands of boho pioneers? And which ethnic group has sole rights to the area? I mean, even before LoHo was Jewish it was probably occupied by Irish or blacks or someone else. Should we go back to a time when it was all Native American? Maybe some Cro-Magnon pre-lapsarian caveman was there before the Indians, and maybe even then scornful voices were raised when modish cave paintings began to put the rents up in the neighbouring caves.

One Tatami, Two Tatami

Because the US economy is booming like never before, Manhattan is the most overvalued piece of land on the planet. Rents here are as high as they were in Tokyo in the 80s. In Tokyo, people measure apartments by tatami mats. Your floorspace is sometimes just two tatamis, or just one. Here in New York I've been seeing a lot of 'bedrooms' which, I swear, are not even big enough for a bed. It's really depressing. I'm realising that I will never fit the 86 boxes of books and electronic junk coming over from my one-bedroom in London into a one-bedroom here, or even a two bedroom. And a one-bedroom in Manhattan costs almost double what I was paying in London.

Because the US economy is booming like never before, Manhattan is the most overvalued piece of land on the planet. Rents here are as high as they were in Tokyo in the 80s. In Tokyo, people measure apartments by tatami mats. Your floorspace is sometimes just two tatamis, or just one. Here in New York I've been seeing a lot of 'bedrooms' which, I swear, are not even big enough for a bed. It's really depressing. I'm realising that I will never fit the 86 boxes of books and electronic junk coming over from my one-bedroom in London into a one-bedroom here, or even a two bedroom. And a one-bedroom in Manhattan costs almost double what I was paying in London.

It's weird, because the areas I'm looking in are poor, slummy areas inhabited by people who barely speak English, and seem incapable of earning the rent. There are two reasons they can afford to be there: rent control and ethnic cronyism. When such people leave, they hand their leases over to friends and colleagues in their own communities, along with the low rents of yesteryear. Chinatown, a place I'd love to live in, seems to work entirely this way. There just aren't any Chinatown apartments in any listings you'll see. They're all for the Chinese. If one does become available, or you get a Chinese-speaking friend to help you find one, the moment the Chinese realtor realises you're not Chinese he'll double the rent. I guess it's some sort of affirmative action. It keeps the area 'funky'.

But as a result the invading creatives have to work twice as hard as the people who run the dry cleaners and the laundromats, just to live in the same rat-infested substandard tenements. Overheard in a cafe in the East Village yesterday, English girl to her American friend: 'I'm sleeping on a kind of shelf, there isn't room for my legs to stretch out straight. It's impossible to control the heat, it's like a sauna in that place. It's totally dark, you never know what time of night or day it is. And it's full of rats and roaches.' I mean, is that FoBo or RealBo? I don't know. It sounds like RealBo to me, but the rents are FoBo. The high rents should make such places the preserve of the affluent, but in fact the shabby conditions make the affluent who choose to live there the new poor. When they've finished paying their two thousand dollars a month for this cramped and funky squalor, they really are poor.

But as a result the invading creatives have to work twice as hard as the people who run the dry cleaners and the laundromats, just to live in the same rat-infested substandard tenements. Overheard in a cafe in the East Village yesterday, English girl to her American friend: 'I'm sleeping on a kind of shelf, there isn't room for my legs to stretch out straight. It's impossible to control the heat, it's like a sauna in that place. It's totally dark, you never know what time of night or day it is. And it's full of rats and roaches.' I mean, is that FoBo or RealBo? I don't know. It sounds like RealBo to me, but the rents are FoBo. The high rents should make such places the preserve of the affluent, but in fact the shabby conditions make the affluent who choose to live there the new poor. When they've finished paying their two thousand dollars a month for this cramped and funky squalor, they really are poor.

But of course the world is their oyster, disposable income or no. The slumming hipster gets to be creative, gets to live meaningfully. Nobody should pity him. Correction: nobody should pity me.

A Rough Guide To Brooklyn

I am currently living in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn, with a view of the south end of Manhattan. (I often just swoosh open my bedroom window and marvel at that jagged, twinkling skyline.) This neighbourhood is full of young middle class families and Italians. It's neither RealBo nor FoBo. It's not at all hip.

I am currently living in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn, with a view of the south end of Manhattan. (I often just swoosh open my bedroom window and marvel at that jagged, twinkling skyline.) This neighbourhood is full of young middle class families and Italians. It's neither RealBo nor FoBo. It's not at all hip.

It's just a temporary stop-gap. I didn't travel thousands of miles to be in Brooklyn. But in my disappointment with the ratty, tatami matty spaces I've been seeing in Manhattan, I am considering some of Brooklyn's funkifying neighbourhoods.

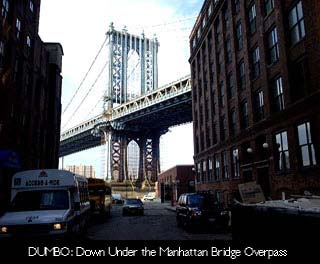

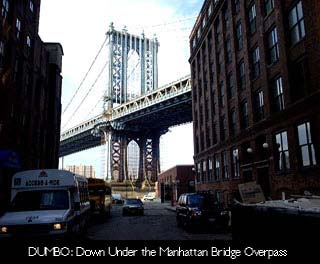

One of them sports one of the memetic acronyms New York is so good at spawning: Dumbo. Which stands for Down Under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass. Dumbo is an area of massive early 20th Century warehouses on the Brooklyn waterfront directly under the gigantic, metallic, pale blue Manhattan Bridge. It's been taken over by artists looking for more reasonable studio space, but is beginning to resemble a new SoHo (which was, suddenly in the 80s, the art neighbourhood but was, just as suddenly in the 90s, replaced in this capacity by Chelsea).

On the Brooklyn side of the Williamsburg Bridge is Williamsburg, which has become an overspill for 20-something creatives who would like to live on the Lower East Side but can't afford the rents. Williamsburg has a very vital little hipster scene. Formerly Polish, it now has a charming, mostly car-free, main street (Bedford Avenue) consisting almost exclusively of cool record stores and comfortable organic cafes occupied by people with hipper-than-thou hairstyles. Every lamp-post has sprouted a chaotic foliage of hand-written ads: 'Couple (French architects) will offer cash reward for large

apartment in this area, call this number'. '2000 square foot loft, stunning waterfront views of Manhattan. Absolutely no living'. There's even the grooviest mall you'll ever see. Instead of JC Penneys and Walmarts, it boasts cred stores full of pink and red ethnic clothes you can wear with trainers, curated selections of used and new indie CDs, and little art galleries filled with sculptures, projections and iMacs.

On the Brooklyn side of the Williamsburg Bridge is Williamsburg, which has become an overspill for 20-something creatives who would like to live on the Lower East Side but can't afford the rents. Williamsburg has a very vital little hipster scene. Formerly Polish, it now has a charming, mostly car-free, main street (Bedford Avenue) consisting almost exclusively of cool record stores and comfortable organic cafes occupied by people with hipper-than-thou hairstyles. Every lamp-post has sprouted a chaotic foliage of hand-written ads: 'Couple (French architects) will offer cash reward for large

apartment in this area, call this number'. '2000 square foot loft, stunning waterfront views of Manhattan. Absolutely no living'. There's even the grooviest mall you'll ever see. Instead of JC Penneys and Walmarts, it boasts cred stores full of pink and red ethnic clothes you can wear with trainers, curated selections of used and new indie CDs, and little art galleries filled with sculptures, projections and iMacs.

Seen on a clothes shop window in Williamsburg, a quote from Gandhi: Be the change you want to see in the world.

Seen on a clothes shop window in Williamsburg, a quote from Gandhi: Be the change you want to see in the world.

Williamsburg is a ghetto, but a nice one, and it's only one stop on the subway to Manhattan.

Never mind the Meatpacking District. Apparently the next hot new neighbourhood, the really wild frontier of property is Harlem. People are complaining that you can't buy cheap buildings there any more, but when I walked around Harlem (pretty, but currently blighted by poverty) all I saw was scary boarded up tenements.

FoBo In LoHo

I feel like there should be some theory here, some definitions, and finally some sort of twist in the tail, but I'm stumped. I don't know what to conclude. Maybe, like Linus Torvalds, I should leave this essay open source and just let people debug it on alt.fan.momus.

So, kids, what do we have here? Bohemia: what happens when people lucky enough to be able to adopt an expressive occupation (call them 'creatives', 'yuppies', 'media content creators', 'hipsters', 'trustafarians' or simply 'us') are forced, by the precarious finances associated with such occupations, to live in poor areas.

FoBo: what results a short while later. When the environmental enrichment which accompanies the arrival of the creatives gets noticed, the area gets rechristened with some snappy acronym like NoLita (North of Little Italy), realtors start charging ludicrous rents, it gets aspirational ('God I would love to live in this boutiquey former slum'), and finally gets replaced, in bodysnatcher pod fashion, by a plastic replica of its former self.

FoBo: what results a short while later. When the environmental enrichment which accompanies the arrival of the creatives gets noticed, the area gets rechristened with some snappy acronym like NoLita (North of Little Italy), realtors start charging ludicrous rents, it gets aspirational ('God I would love to live in this boutiquey former slum'), and finally gets replaced, in bodysnatcher pod fashion, by a plastic replica of its former self.

But FoBo is also what happens when a society evolves to the point at which artists get the recognition and the payment they deserve. Artists only get rich when societies accept that communication at high levels is important. Shelley said that artists were the unacknowledged legislators of the world. Nietzsche said they should rule. Maybe now, at least in a city like New York, they do. But we should remember that artists only get rich thanks to a sophisticated system of galleries and dealers, and a legal framework which asserts and protects copyright. Without those things, artists would be right back in the ghetto.

Formerly Radical, Now Just Chic

I've been getting a laugh by telling people that FoBo, Faux Bohemia, is what I'm looking for. 'I'm quite happy to let other people do all the dirty work for me. I just want to move in when an area is safe, when Japanese kids living on their parents' money have taken apartments there, when you can buy Tom Dixon lamps and ironic secondhand clothes there, when there's an Apple dealer on the corner'. Of course it helps to have groovy nightspots on your doorstep too, like LoHo's Tonic, where I went the other night, or even Jonas Mekas' Underground Film Archive.

People laugh, but I mean it. I like places which were once known for the plastic arts but ended up just plastic. My snobbery about this is purely inverse, it's the opposite of the snobbery in the Village Voice. I lived in Montmartre eighty years after Picasso and the gang abandoned it for Montparnasse. I lived in London's Chelsea long after Granny Takes A Trip took a trip, leaving it for undrugged grannies and branches of Next. Those are my places, and they're girly places, gay places, places where you feel safe. I can live there because I actually have no insecurities, financial or psychological, about my status as an artist. I don't need to prove I'm an artist by living somewhere shitty and making no money.

People laugh, but I mean it. I like places which were once known for the plastic arts but ended up just plastic. My snobbery about this is purely inverse, it's the opposite of the snobbery in the Village Voice. I lived in Montmartre eighty years after Picasso and the gang abandoned it for Montparnasse. I lived in London's Chelsea long after Granny Takes A Trip took a trip, leaving it for undrugged grannies and branches of Next. Those are my places, and they're girly places, gay places, places where you feel safe. I can live there because I actually have no insecurities, financial or psychological, about my status as an artist. I don't need to prove I'm an artist by living somewhere shitty and making no money.

I make such places creative again by composing records there which revive their glorious creative heydays. Records at once electronic and sepia tinted. Records which mine academic histories of cabaret, or take their tone from places like the Museum of Montmartre, the Museum of London or the Lower East Side Tenement Museum. I'm a museum kinda guy. I like simulacra.

But that's because I live in Plato's cave, and prefer shadows to the sun. That's because I'm Des Esseintes from Huysmans' 'Against Nature' and prefer ethnic restaurant decor to the authentic culture it seems to represent. Because I'm totally, like, FoBo, daddy-o.

But what's going to happen if we all go post-copyright? I mean, I can afford the formerly-radical, now chic districts only because of record and publishing contracts. But if, as I preach on the panels of music conferences, we're all going to be living on ancillary revenue streams and love in the new Attention Economy, maybe I'll have to start living in poor areas again. Genuinely poor wilderness places like The Bronx, sprinkled here and there with a tiny elite of semi-visible urban pioneers.

God forbid, maybe I'll have to return to the cutting edge. At least until landlords also start living on attention, ancillary revenue streams and love.

God forbid, maybe I'll have to return to the cutting edge. At least until landlords also start living on attention, ancillary revenue streams and love.

Thoughts Index

Index

'If a thing's worth doing, it's worth doing badly (baby)' sang Green of Scritti Politti. You could add that if a thing's worth doing, it's worth doing for no money. A phrase that seemed to keep coming up at the New York Expo music and technology conference earlier this month was 'ancillary revenue streams'. As in Q: How can artists survive in a post-copyright age, where their music may well be given away online for nothing? A: Ancillary revenue streams. Which means that even if the music's free, you can still sell people T shirts, or put banner ads on your website, or get paid to present the Grammys, based on your status as a cult music maker.

'If a thing's worth doing, it's worth doing badly (baby)' sang Green of Scritti Politti. You could add that if a thing's worth doing, it's worth doing for no money. A phrase that seemed to keep coming up at the New York Expo music and technology conference earlier this month was 'ancillary revenue streams'. As in Q: How can artists survive in a post-copyright age, where their music may well be given away online for nothing? A: Ancillary revenue streams. Which means that even if the music's free, you can still sell people T shirts, or put banner ads on your website, or get paid to present the Grammys, based on your status as a cult music maker. Are we really returning to folk music? Is art going to be communal, copyright unenforceable? Am I one of the last people to make a living from ideas?

Are we really returning to folk music? Is art going to be communal, copyright unenforceable? Am I one of the last people to make a living from ideas? FoBo is Faux Bohemia. It's rich people deciding to slum it and live amongst the poor, only to force the poor out of the area. It's rents skyrocketing because an area is being occupied by artists (who only, poor dears, went there in the first place because it was such a godforsaken wilderness where even people who made virtually no money could pay the rent). FoBo is those same areas a few years after their embourgeoisement, sporting an increasingly tame and plastic air of radical bohemia. It's a fading memory of cutting-edge relevance. It's a Greenwich Village coffee house, it's a SoHo loft.

FoBo is Faux Bohemia. It's rich people deciding to slum it and live amongst the poor, only to force the poor out of the area. It's rents skyrocketing because an area is being occupied by artists (who only, poor dears, went there in the first place because it was such a godforsaken wilderness where even people who made virtually no money could pay the rent). FoBo is those same areas a few years after their embourgeoisement, sporting an increasingly tame and plastic air of radical bohemia. It's a fading memory of cutting-edge relevance. It's a Greenwich Village coffee house, it's a SoHo loft. The Voice article about the 'boutiquification' of LoHo assumed the tone of all Golden Ageists and Holier-Than-Thou pioneers. It basically said that the area was once, for hipsters at least, a kind of wild frontier. When Reed and Cale lived on Ludlow Street they had a cold water walk-up. They stole electricity from next door through a secret cable. Now the place is full of 'media content creators' taking refuge from the multimedia companies of the Flatiron District, or Financial people cashing in on the proximity to Wall Street.

The Voice article about the 'boutiquification' of LoHo assumed the tone of all Golden Ageists and Holier-Than-Thou pioneers. It basically said that the area was once, for hipsters at least, a kind of wild frontier. When Reed and Cale lived on Ludlow Street they had a cold water walk-up. They stole electricity from next door through a secret cable. Now the place is full of 'media content creators' taking refuge from the multimedia companies of the Flatiron District, or Financial people cashing in on the proximity to Wall Street. Because the US economy is booming like never before, Manhattan is the most overvalued piece of land on the planet. Rents here are as high as they were in Tokyo in the 80s. In Tokyo, people measure apartments by tatami mats. Your floorspace is sometimes just two tatamis, or just one. Here in New York I've been seeing a lot of 'bedrooms' which, I swear, are not even big enough for a bed. It's really depressing. I'm realising that I will never fit the 86 boxes of books and electronic junk coming over from my one-bedroom in London into a one-bedroom here, or even a two bedroom. And a one-bedroom in Manhattan costs almost double what I was paying in London.

Because the US economy is booming like never before, Manhattan is the most overvalued piece of land on the planet. Rents here are as high as they were in Tokyo in the 80s. In Tokyo, people measure apartments by tatami mats. Your floorspace is sometimes just two tatamis, or just one. Here in New York I've been seeing a lot of 'bedrooms' which, I swear, are not even big enough for a bed. It's really depressing. I'm realising that I will never fit the 86 boxes of books and electronic junk coming over from my one-bedroom in London into a one-bedroom here, or even a two bedroom. And a one-bedroom in Manhattan costs almost double what I was paying in London. But as a result the invading creatives have to work twice as hard as the people who run the dry cleaners and the laundromats, just to live in the same rat-infested substandard tenements. Overheard in a cafe in the East Village yesterday, English girl to her American friend: 'I'm sleeping on a kind of shelf, there isn't room for my legs to stretch out straight. It's impossible to control the heat, it's like a sauna in that place. It's totally dark, you never know what time of night or day it is. And it's full of rats and roaches.' I mean, is that FoBo or RealBo? I don't know. It sounds like RealBo to me, but the rents are FoBo. The high rents should make such places the preserve of the affluent, but in fact the shabby conditions make the affluent who choose to live there the new poor. When they've finished paying their two thousand dollars a month for this cramped and funky squalor, they really are poor.

But as a result the invading creatives have to work twice as hard as the people who run the dry cleaners and the laundromats, just to live in the same rat-infested substandard tenements. Overheard in a cafe in the East Village yesterday, English girl to her American friend: 'I'm sleeping on a kind of shelf, there isn't room for my legs to stretch out straight. It's impossible to control the heat, it's like a sauna in that place. It's totally dark, you never know what time of night or day it is. And it's full of rats and roaches.' I mean, is that FoBo or RealBo? I don't know. It sounds like RealBo to me, but the rents are FoBo. The high rents should make such places the preserve of the affluent, but in fact the shabby conditions make the affluent who choose to live there the new poor. When they've finished paying their two thousand dollars a month for this cramped and funky squalor, they really are poor. I am currently living in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn, with a view of the south end of Manhattan. (I often just swoosh open my bedroom window and marvel at that jagged, twinkling skyline.) This neighbourhood is full of young middle class families and Italians. It's neither RealBo nor FoBo. It's not at all hip.

I am currently living in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn, with a view of the south end of Manhattan. (I often just swoosh open my bedroom window and marvel at that jagged, twinkling skyline.) This neighbourhood is full of young middle class families and Italians. It's neither RealBo nor FoBo. It's not at all hip. On the Brooklyn side of the Williamsburg Bridge is Williamsburg, which has become an overspill for 20-something creatives who would like to live on the Lower East Side but can't afford the rents. Williamsburg has a very vital little hipster scene. Formerly Polish, it now has a charming, mostly car-free, main street (Bedford Avenue) consisting almost exclusively of cool record stores and comfortable organic cafes occupied by people with hipper-than-thou hairstyles. Every lamp-post has sprouted a chaotic foliage of hand-written ads: 'Couple (French architects) will offer cash reward for large

apartment in this area, call this number'. '2000 square foot loft, stunning waterfront views of Manhattan. Absolutely no living'. There's even the grooviest mall you'll ever see. Instead of JC Penneys and Walmarts, it boasts cred stores full of pink and red ethnic clothes you can wear with trainers, curated selections of used and new indie CDs, and little art galleries filled with sculptures, projections and iMacs.

On the Brooklyn side of the Williamsburg Bridge is Williamsburg, which has become an overspill for 20-something creatives who would like to live on the Lower East Side but can't afford the rents. Williamsburg has a very vital little hipster scene. Formerly Polish, it now has a charming, mostly car-free, main street (Bedford Avenue) consisting almost exclusively of cool record stores and comfortable organic cafes occupied by people with hipper-than-thou hairstyles. Every lamp-post has sprouted a chaotic foliage of hand-written ads: 'Couple (French architects) will offer cash reward for large

apartment in this area, call this number'. '2000 square foot loft, stunning waterfront views of Manhattan. Absolutely no living'. There's even the grooviest mall you'll ever see. Instead of JC Penneys and Walmarts, it boasts cred stores full of pink and red ethnic clothes you can wear with trainers, curated selections of used and new indie CDs, and little art galleries filled with sculptures, projections and iMacs. Seen on a clothes shop window in Williamsburg, a quote from Gandhi: Be the change you want to see in the world.

Seen on a clothes shop window in Williamsburg, a quote from Gandhi: Be the change you want to see in the world. FoBo: what results a short while later. When the environmental enrichment which accompanies the arrival of the creatives gets noticed, the area gets rechristened with some snappy acronym like NoLita (North of Little Italy), realtors start charging ludicrous rents, it gets aspirational ('God I would love to live in this boutiquey former slum'), and finally gets replaced, in bodysnatcher pod fashion, by a plastic replica of its former self.

FoBo: what results a short while later. When the environmental enrichment which accompanies the arrival of the creatives gets noticed, the area gets rechristened with some snappy acronym like NoLita (North of Little Italy), realtors start charging ludicrous rents, it gets aspirational ('God I would love to live in this boutiquey former slum'), and finally gets replaced, in bodysnatcher pod fashion, by a plastic replica of its former self. People laugh, but I mean it. I like places which were once known for the plastic arts but ended up just plastic. My snobbery about this is purely inverse, it's the opposite of the snobbery in the Village Voice. I lived in Montmartre eighty years after Picasso and the gang abandoned it for Montparnasse. I lived in London's Chelsea long after Granny Takes A Trip took a trip, leaving it for undrugged grannies and branches of Next. Those are my places, and they're girly places, gay places, places where you feel safe. I can live there because I actually have no insecurities, financial or psychological, about my status as an artist. I don't need to prove I'm an artist by living somewhere shitty and making no money.

People laugh, but I mean it. I like places which were once known for the plastic arts but ended up just plastic. My snobbery about this is purely inverse, it's the opposite of the snobbery in the Village Voice. I lived in Montmartre eighty years after Picasso and the gang abandoned it for Montparnasse. I lived in London's Chelsea long after Granny Takes A Trip took a trip, leaving it for undrugged grannies and branches of Next. Those are my places, and they're girly places, gay places, places where you feel safe. I can live there because I actually have no insecurities, financial or psychological, about my status as an artist. I don't need to prove I'm an artist by living somewhere shitty and making no money. God forbid, maybe I'll have to return to the cutting edge. At least until landlords also start living on attention, ancillary revenue streams and love.

God forbid, maybe I'll have to return to the cutting edge. At least until landlords also start living on attention, ancillary revenue streams and love.